poems by rachel kellum

to comment ✒️ click on a title

Past Fifty

Who knew I would feel

young? Except in

my bones, poor posture,

parched mornings

after nights of bottles

with mountain poets,

patio music, chosen brothers,

liberated sister-mothers

toasting the post pandemic

opening of this

end of the road town.

How can I say it?

I used to run and run.

I know that high.

My body did my bidding.

And so much wanting.

Such a drug. It wanes.

The constant longing

for more than life

can offer a young mother

already rich with children.

Joy and regret.

Strange bedfellows.

All of that in me today

in the quiet, and my love

dozing here on the sofa,

his long legs draped across

my lap, hands folded

on his belly, head tilted up

on a pillow, beautiful

in that awful pose.

We both and all of us

are for the pyre.

It’s not a metaphor.

We’ve watched it burn.

Absorbed its warmth.

But now! We are alive,

my love and I, these bones,

turning to look at each other

from time to time,

my writing arm in the sun.

The Wayback Machine

Sally Jane Seck is not only my web guru but also a time wizard. She found The Wayback Machine, an internet archive with snapshots of all kinds of old wordweeds content. This discovery is strangely comforting, like the time I found out my old dog Mojo hadn’t yet been cremated weeks after her death and was still curled up as if in an afternoon snooze in the vet office deep freeze. I got to say a second goodbye. B minus Buddhist that I am, I have a hard time letting things go sometimes. Now I can say a proper farewell. Here’s the old wordweeds homepage featuring a 10/10/2020 post. Rest in peace, WW.

Fish Heads

after Raymond Carver

Ted Fish made heads out of clay.

He was known for it, loved.

These heads are all over Salida.

Pinch lipped busts in shop windows.

Bobbing ornaments in dead trees.

One, a skinless, meat-red monolith

sits on a bank among boulders,

casting the line of its low gaze

over the Arkansas, a marker

for boaters to measure depth.

I never knew him except through

others’ grief. He died a few

weeks before I moved there.

On the table. Under the knife.

His heart.

Two heads came into my hands

in round about ways. One

from a new friend, fellow artist

and co-worker, Ben, whose

eyes teared up when he handed

it to me, a porcelain, grimacing,

two-faced thing with a hole

clear through the crown to

the throat, passage for some jute

rope I’ve planned for years to string

with fat, glass beads the color

of Caribbean swells. Maybe

I’ll finally get to it. After a story,

Barbara, poet who refuses

public farewells and left his funeral

early, gave me the other: a black face—

blue edged, sort of grinning—emerging

from white porcelain slab. The whole

thing attached to a small black canvas

with two long copper wire stitches.

I placed it on the piano where sheet

music should perch. The piano

is always out of tune, but my son

plays it anyway. Two nights ago,

on a stop as he was driving through,

the tiny head rang, watery

with my son’s invented song.

When I hugged him hello

and later goodbye, hard, I felt him

tremble, quaking in the core, a dark

face pressing through his body

into mine. In the kitchen, he talked

in low, steady tones, like there

was earth under his feet, said

when he gets back he’s drying out,

going to stop filling the hole

with every dead sailor in the sea.

“You can do it,” I said, “change karma,

consequence.” Which was too much,

another hole. You can do it is all I meant,

but saying less is hard for me. He knows.

“Thank you,” he said, and for a second,

soft eyed, lost himself among crumbs

on the counter. Then raised his head.

Buddha Woman Speaks and Surrenders, Again

Oh, it is you again

standing here within me,

dancing the darkest moon of my dish

washing, gnawing my hipped belly bowl

promising blood.

You tango through the terror

of my uninhabited dreams, rip

the seams of me where these

clothes don’t fit, haven’t fit

for years of moons at many sinks.

I try not to think about it, but you,

Blood Woman, you needle

to keep me true to who

I think I am, or wanted to be,

but I am always changing, see?

We never agree. You say throw the plates!

I say make them gleam.

I am tired of our existential arguing.

Of cutting myself in pieces for your uses:

Mother, writer, sister, teacher, lover, painter, blue.

You are ruthless, refuse to let me lose these faces.

If only we could multiply our tongue by two!

If only they could flap at once,

in absolute and relative bliss,

Laughing: this/not this! this/not this!

But you won’t have it.

You insist: this, this, this!

I can’t resist. I drop a dish.

2008

featured in Slow Trains, 2008

vestige of an old friend

It’s been two intensive weeks of moving twelve years worth (820-some posts!) of wordweeds content from Wordpress to this new, more functional and, hopefully, more beautiful Squarespace site. With the expert help of my web guru, the incomparable poet Sally Seck, it was a fairly simple, joyful process to witness the ease with which all content (posts, comments, photos, pages, categories, dates, archives, etc.), slid right into their new home without a hitch but one: every single poem had decided to throw off the clothing of line breaks and stanzas and start their new lives as chunky, naked little prose poems. Hence began the face-melting, time consuming task of cutting and pasting, cutting and pasting previously formatted poems into the new site. It was a labor of love, as they say, a gentle reckoning to handle the cloth of poems written as far back as the late 1990s, travel through the sunshine and storms of the twenty-oughts and -tens up to now. I’m grateful for the opportunity to go back and re-read what has become a rather large body of work, my body. I’m mixing metaphors now.

A pang of grief shocked through me when I successfully transferred the wordweeds.com domain name to the new site, clicked refresh, and realized my old site was gone forever. Poof. She was a dear friend and curator of my poetry life for over a decade. I miss her already, the funny way she dressed.

I wish I had snapped a screenshot of that adorably circa 2010 homepage design, with its long scarf of a navigation bar hanging along the right arm of the page, forcing me to make short line breaks. It’ll be nice to have more room to stretch out here.

This image of the homepage header will have to do: a business card that has always better served as a book mark.

For now these hot days is the mad blood stirring…

My Mad Blood

I’m thrilled to have ten poems featured in Mad Blood #7!

Much thanks to the gifted poet and publisher Padma Thornlyre for putting this gorgeous collection together in a trying time.

Affording Sugar

On mother’s day I’m up early,

peeking in on my child,

wiping up cat vomit, sharing

yesterday’s beet scraps

with five chickens in the run,

feeding two dogs who never tire

of my touch. My husband

and youngest son, who arrived

last night while I slept,

are still asleep, bless them,

giant men whose lives happen

above my head, witnessing

the dusty tops of fridges

everywhere they go. They know.

I’m down here, whisking matcha,

marveling at cedar shadows

quaking across dusty windows,

a sun rising through smoke

over the Sangres, boiling

four parts water to one part

sugar for the hummingbird

we heard zipping about this week,

looking for our sweet life, the one

my grandmother gave me

growing my sweet mother inside,

whose tiny body already cradled

all the eggs she’d ever release,

including me, so lucky.

Self-Interview in The Nervous Breakdown

This interview was published in The Nervous Breakdown on January 15, 2013. I bumped into it again while migrating content from the old wordweeds website. Enjoy!

You’ve been awfully quiet today. What’s up?

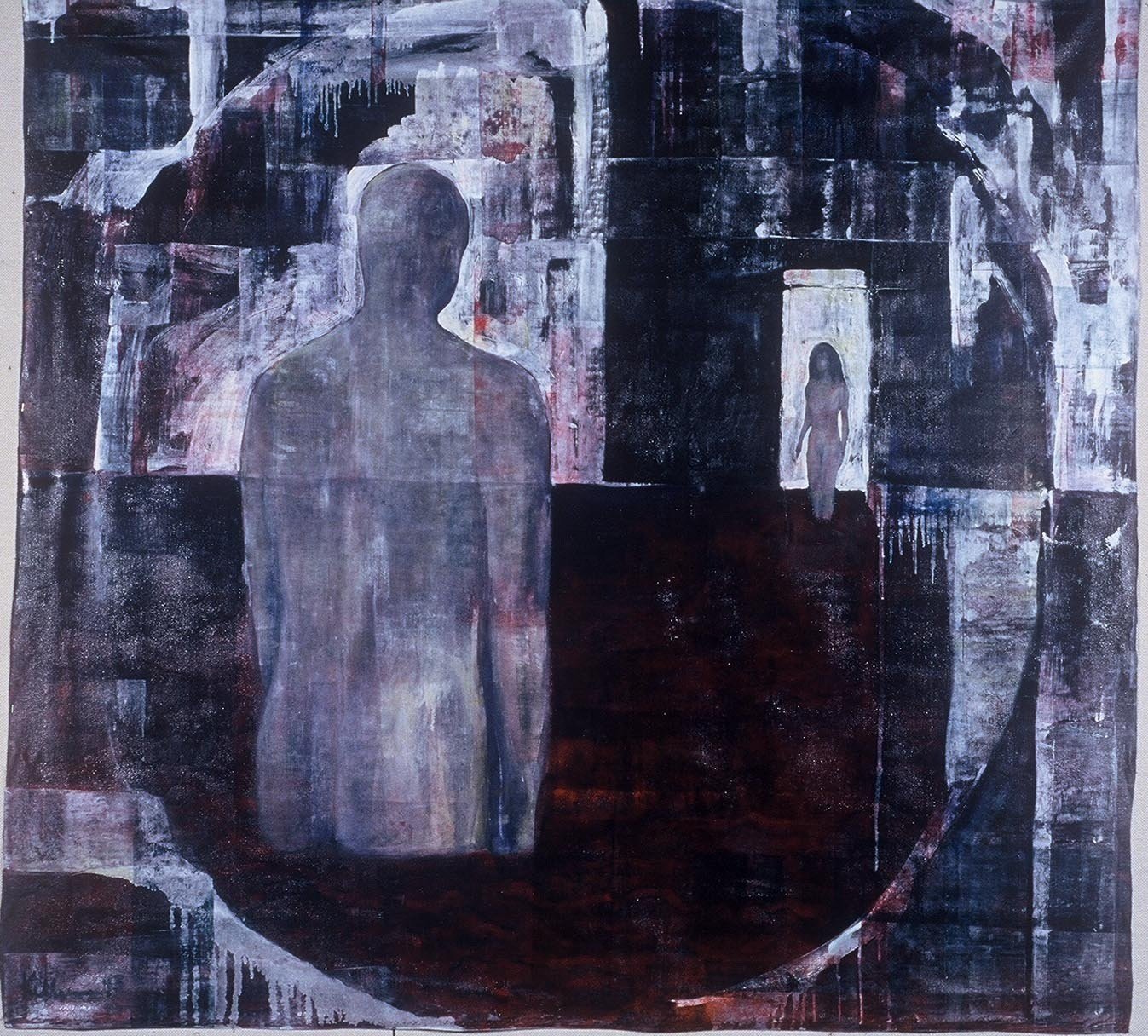

I’ve been thinking of my attraction to bardo spaces. The in-between places. I suppose I’ve been dancing there since my early 20s when I left organized religion and began formally pursuing the visual and literary arts. An early exhibit of oils and monotypes called Between featured quasi-mythological, autobiographical figures knee-deep to chest-high in water, both on land and at sea at once. Looking back, it isn’t a surprise that ten years later I would begin seriously studying Tibetan Buddhism where this concept of the between figures prominently. It’s a natural fit for me. Any philosophy that makes a practice out of living beyond duality and with the concept of both/and feels like home.

-

After all this time would you say this philosophy still informs your aesthetic sensibility?

Yes, probably more than anything else.

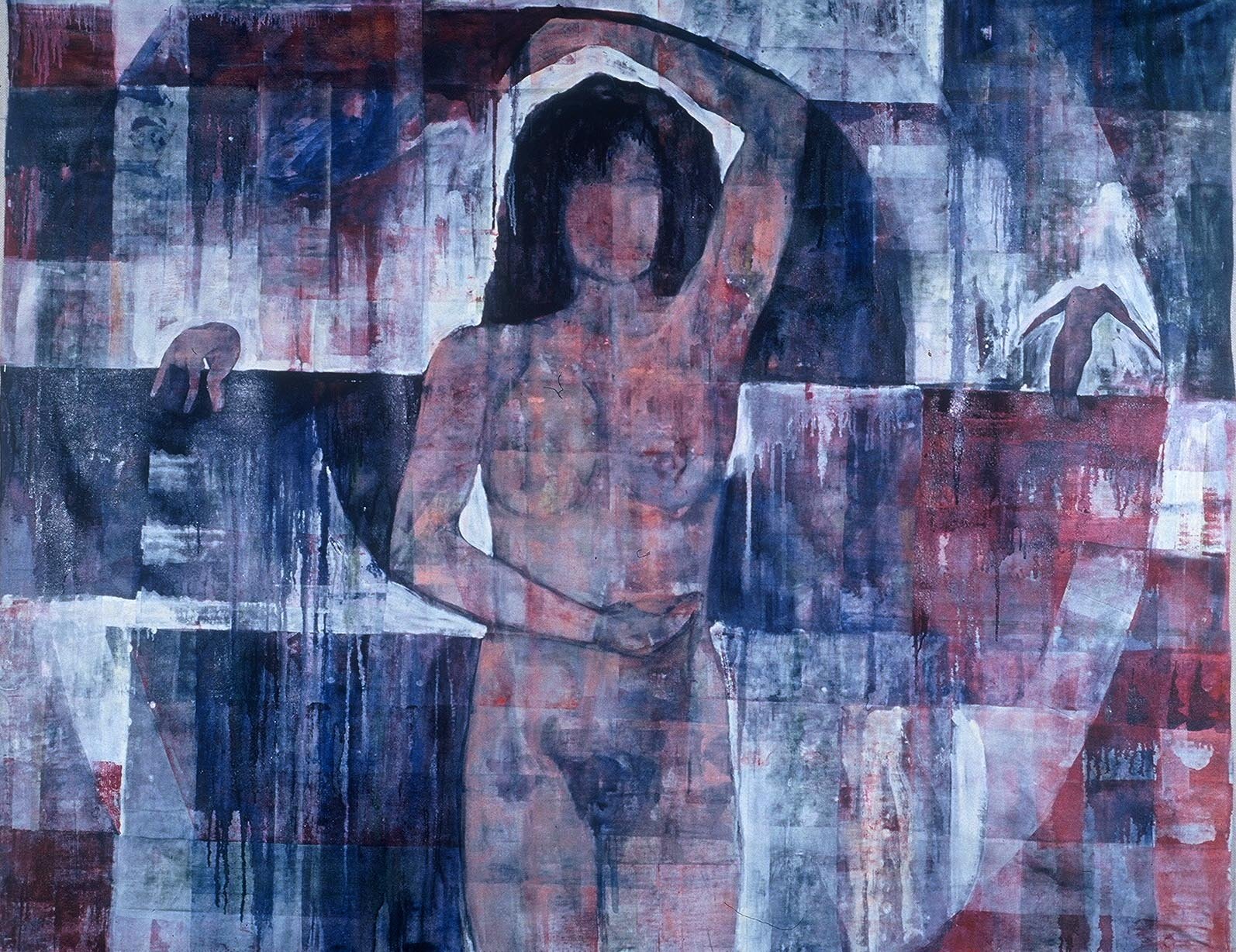

In the visual arts it manifests in the media I’ve explored, like monotyping—a place between painting and printmaking. Though I don’t have access to a press anymore, and I’m mostly focusing on figure painting, the techniques I used as a monotypist are still at play in my paintings, which consist of layering expressive textures of shape and color, usually very simple, nonlocal color, and then subtracting paint with rags. I’ve been told my work has a Modernist feel, and that makes sense, given my interest in not only the poetic but also artistic innovations of that time, namely Fauvism and Expressionism—cusp movements that sought to break with traditional representation in favor of bringing more attention to the act of painting and the medium’s expressive potential.

I’ve never verbalized it until now, but even the fact that I can’t seem to pull away from representing the nude is another kind of bardo fascination. The studio figure is a rather in-between creature, especially nude, and is fraught with a controversial subject/object history. Because they exist in a kind of mythic, aesthetic, erotic limbo, nude figures don’t seem to belong anywhere. This captivates me. There are all kinds of vulnerabilities and creativities, psychospiritual and geosexual political possibilities in not fully belonging somewhere or to someone. In the act of painting, I experience these figures as abstractions of such possibilities, abstractions of myself, even. There’s a breakdown in the subject/object dichotomy. It’s a very visceral experience.

That sounded very ivory tower and mystical all at once. Well done. What about poetry?

I would say most of my work falls in between free verse and form, which might mean that from either of those perspectives, I won’t make anyone completely happy. I like the freedom of not being married to meter and rhyme, but I flirt with both by employing tons of assonance and loose patterns of rhythm and line length. Some visual form, melody of sound and rhythm usually emerge, but never fully gel. And then there is the matter of content. Most of my work circles some hesitant nuptial between polarities: sacred and profane, self and other, male and female, gay and straight, infidelity and loyalty, natural and artificial, science and mysticism, presence and absence, independence and dependence, freedom and confinement. The list could go on.

Do you ever combine your poetry with your visual art?

Not often. Many years ago I wallpapered a gallery with collected and original writings. That pissed off a couple of my art professors. I’ve also done an oil self-portrait with shreds of my poetry collaged into it. And last year I gave a reading with two large abstract paintings as backdrops, but other than that, I haven’t explored it as much as I’d like to. Perhaps the marriage comes in bringing a visual sensibility to poetry, and a poetic sensibility to painting.

You’ve used a marriage metaphor three times now. What’s going on?

Hmm. I’m intrigued by figurative marriage—perhaps the ultimate metaphor for the natural state of things. I can see why people are so drawn to literal marriage, the urge to enact that state in a very concrete way. I admire people who do it well and feel compassion for those who struggle with it. I suppose the bardo principle also rules my relationships, my attractions to other human beings. I’m not sure how I feel about this, or if this is at all a good thing.

Why cultivate it then?

I’m more at ease in the between, and when I think I could settle in one place for long, I tend to slide out, or to at least want to very badly. Actually, I’m not so sure I am at ease being this way. Enlivened is perhaps the better word. Bardo places can be very uncomfortable in a world where staying put helps the gears turn more easily, but there is an irresistible power there. A creative power. I think the truth is we are all in between something or other. How aware we are of the fact, or how much we fight or embrace our tendencies toward extremes of solidity might be directly related to how much we suffer.

Don’t take this personally, but does TNB really understand what they are getting into by asking a Buddhist to interview herself?

Who is asking me this question?

Who is answering it?

Ah….hm.

Sneaky segue. And a little corny, I might add.

Oh! That was a spontaneous “ah,” I swear. But it just so happens that ah is the title of my first book, and you might want to ask me about it. Besides, Rosemerry suggested you ask what I am most afraid of when I think of people reading this interview, so we might as well get that out of the way while I’m shamelessly self-promoting my book: fear of being perceived as corny.

Hey, I’m supposed to ask the questions, not Rosemerry.

What’s the difference? We love her. She also suggested you ask me what I wish we would not talk about.

You are being controlling.

I’m just offering suggestions. So, do you want me to answer that one?

No.

Ok.

Can we start over here?

Always.

So, what do people need to know about ah?

Its genesis is largely described in the opening notes to the book, but I’m happy to explain a bit here. In 2010 I had begun studying a collection of poetic meditation instructions written by ancient Dzogchen masters of the Bön Buddhist tradition. By the summer of 2011, it occurred to me it would be interesting to attempt to write my own poetic reflections on this practice. So, basically, the poems that became ah were simply a prolonged exercise in using one mindfulness practice, poetry, to clarify another, Dzogchen. Or maybe it is the other way around.

I didn’t plan on arranging the poems into a book until Markiah Friedman of Liquid Light Press invited me to send him a manuscript after seeing me perform a couple of them on his Poet’s Co-op TV show. I live in a very conservative part of Colorado and hadn’t read them to anyone there yet. Reading the poems for Markiah and three cameras not far from Buddhist-friendly Boulder made me, um, bolder. I’m glad I took the risk. It turns out Liquid Light Press is dedicated to publishing poetry that explores realms of spiritual experience with an attention to craft. It’s a great venue for poetry that usually doesn’t have a place in more academically focused publications. Liquid Light Press is one of those in-between places I love.

Can you say something about Dzogchen?

Sure. The word itself means great perfection and is so simple, experiential and nonconceptual, it’s a little hard to explain. Practically speaking, it’s a kind of meditation practice whose purpose is to help us rest in what is called our natural mind. It is said our minds are naturally spacious and clear. But it’s hard to relax into this state without a little help. Hence the instructions. Hence the practice. It’s not about getting rid of thoughts, though. That’s impossible. It’s more about changing our relationship with the thoughts, emotions, words and images that run around in us. In practice, they might still gallop about at first, but we don’t ride off on them. Eventually they nestle down for a nap. When they stir, we gently notice. Without any effort on our part, the animals come and go, arise and dissolve, of their own accord, and we learn to rest in this subtle movement without judgment or nihilism. I’ve used a metaphor here, but promise me you’ll forget it. There’s room for everything in this place. I like to go there. I think most people might like to, regardless of their personal belief system or lack thereof.

Watch yourself, Sister Kellum.

That’s funny. I know with our Mormon upbringing you worry about people thinking you are trying to convert them or something, but you and I both know this isn’t about religion but sanity. Most of us are pretty busy-headed. Who doesn’t want a break from that? Everybody deserves some respite from, some perspective on, the entertaining tango of their own horseshit and glory no matter how they come by it. I’ve found that when I come back to the mundane world after a successful practice, creativity comes more spontaneously. Words flow. Crafting and revising is a joy. Though these aren’t the reasons I practice, I love these perks, and that’s how most of the ah poems were born. Not all of them are about being open and spacious (which is what ah, or the Tibetan letter a, means, by the way). Many of these poems are actually just my mind rustling words instead of resting in space.

Isn’t writing conceptually about something that is meant to be a nonconceptual experience kind of counterproductive?

Probably. The great irony of writing this book and then memorizing many of the poems for performance is that they have become obstacles to my meditation practice. Shortly after a performance, when I’m on the cushion, a few of the clearer poems prance around, proudly pontificating about my natural state, and then I miss out on the experience completely. The ego is so tricky. So, not taking these poems too seriously has become another layer of my practice. I’ve had to let them go, or stop riding off into the sunset on them, at least.

I thought you said you left behind organized religion. You sound pretty seriously involved with this Bön stuff.

I know. I don’t want to talk about that too much. Discussing my dedication to the Bön tradition always makes me a little nervous. And to be honest, having my book out there only compounds that feeling because I don’t want pegged as someone setting herself up as some kind of guru, on one hand, or as only a Bön poet, on the other. It’s a bardo book for me—not fully at home in the world of Buddhists or poets; though, it was a fine moment to share a few of these poems with my teacher and sangha at the end of September this year.

I should say here that most of my poems, outside of ah, are not about meditation practice at all, though it is true my poetry is driven by the undeniable need to bring awareness to my living. I’m not sure why I suddenly feel this urge to defend myself. I’m a word-addicted person who needs serious help with this fact. My head rarely shuts up. That’s a good reason to practice. Can we talk about something else now?

Sure. What?

I want to say that yesterday I raked leaves with my three big kids, ages 10, 13 and 18—two of them are my size now—and I was grumpy almost the whole time. We have two dogs, and doing poop patrol in the midst of brown leaves is the worst kind of Where’s Waldo. Sam, the youngest, helped me with this awful task without complaining. We wore plastic grocery sacks on our hands. My two oldest kids, without my guidance, figured out the coolest way to bag leaves quickly. Grey held two rakes parallel to his arms and scooped up leaves like the most efficient Edward Scissorhandsian boymachine (Sam asked, “Isn’t that a scary movie?” and Grey said, “No, I think you are confusing horror with horrible.”), while Sage used a five gallon bucket to repeatedly compress leaves in the garbage can. I took over when Sage had to leave for work. All told, there were 24 bags, and we finished in just a couple hours. I’m sore. I’m psyched my kids are so smart and helpful when they aren’t texting or Facebooking and playing Minecraft. I can’t believe these huge beings came out of me, talk to me, critique films, and help rake leaves. I admire their ability to inhabit both digital and analog worlds quite joyfully. They had me laughing by the end of the chore.

Do you write about them much?

Sometimes. I’ve always loved how Robert Hass writes about his kids. One poem in Human Wishes, the first book of his I ever owned, reveals a moment when his son, Leif, tells him, “Dad,[…] I’m not taking any more/ of this tyrannical bullshit.” And when Hass responds by reading a line from Chia Ya, the boys adds, “And another thing, don’t lay/ your Buddhist trips on me.” I hope my work is as honest as that. I have collected almost everything he’s written. Our styles are quite different, but I adore Hass, his catalogues of observation. He isn’t corny at all. His long lines have carried on a low conversation with what is hardest in me for many years. There is a natural, honest rhythm in them that I’m always aiming for. In his essay, “Rhythm and Making,” he tells us, “Because rhythm has direct access to the unconscious, because it can hypnotize us, enter our bodies and make us move, it is a power. And power is always political. That is why rhythm is always revolutionary ground.” Mmm. Such words inspire gratitude for all the poets and song writers whose rhythms have revolved and evolved me over the years: Hass, of course, and Eliot, Roethke, Stevens, Whitman, Ginsberg, Chris Whitley, Ani Difranco, Greg Brown, and a generous and gifted family of Colorado poets who play at words with me.

One more thing about Hass. In the mid-90s, a guy in a local Fort Collins bookstore helped me locate him on the shelf. He informed me he didn’t like Hass’s work; it was too privileged, not political enough. As a graduate student at the time, I thought there must be something to what he said.

I bought Human Wishes anyway.

The night before I turned 51

I dreamed my father next to me

holding my hand through a parking lot,

his full cheeked smile held inside

those radiating parentheses reaching

out like endless arms from his eyes—

like mine in the brightest sunlight,

caught laughing in a rearview mirror.

(I learned to love my smile by loving his.)

We walked like this toward some store

I wanted to avoid, so he wouldn’t feel

he had to buy me something, the coat

I wanted, or some other ephemeral

thready thing to make up for a lifetime

of missing him, missing him, missing him.

I rehearsed in my mind what I wanted

him to know: I forgive you every day.

I woke before I said it, distracted by

a gallery of Japanese woodcut prints,

one of them a curious face watching us

pass as I noticed us drift across glass.